WWI centenary: Diary tells of bravery of the troops

More than 34,000 British troops were killed during the Gallipoli campaign and 78,000 were wounded.

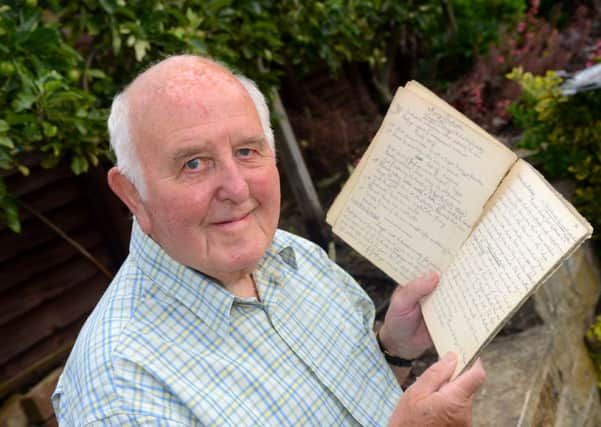

But a diary now in the possession of Mirfield man Norris Handford tells a different story.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe diary belonged to his father, George Albert Handford, who recounts a tale of allied bravery in the face of a Turkish onslaught, sweltering heat and disease running rife. George told how he was living in a “small hamlet in Yorkshire” – Mirfield – and working on the railways when war was declared.

He signed up aged 21 and gave a detailed account of his journey to the Dardenelles, where a Austrian submarine torpedo missed their ship by yards.

George and his comrades in the Eighth Duke of Wellington Regiment formed part of the August offensive, five months after the campaign started.

Approaching the Gallipoli peninsula, they waited until night to attack the beach at Sulva Bay. The men were met with light opposition, but were still under fire and George did not have the best start.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe wrote: “Arrived at the beach we could discern figures in front of us, orders were being given everywhere to disembark. However that was the last order I heard for somebody’s rifle, having being hit by the enemy, caught me in the face and I was politely knocked into the sea.

“A cold reception, which I think did me a lot of good, and then I felt somebody’s hand clutching to help me up. Pulling myself together and making for the beach I joined in with the lads to help force the landing. Having lost my bayonet rifle I soon picked up another of a fallen comrade.”

After the initial burst, the allies were unable to make much progress – mines littered the land and enemy snipers lay in wait.

The Ottomans were able to occupy the Anafarta Hills, preventing the British from penetrating inland, which reduced the Suvla front to static trench warfare.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdA further attack by George’s unit saw their number reduced from 100 to 60 as they were surrounded by Turks.

George explained: “For four nights and days we stayed here keeping our eyes skimmed and believe me had not re-reinforcements arrived I don’t think there would have been anyone left to tell the tale.”

Stationed in what would become known as the Chocolate Hill trenches, George described the ongoing battle to get enough water to drink. “Nobody knows the value of water only those poor devils who have had to pine for it,” he wrote.

A walk to the nearest well was around three miles, and once there, a thirsty solider would find snipers trained on the well. He went on: “Often though, driven to desperation through thirst, men would go and chance what may be their fate, so therefore one cannot wonder why all round these wells were piled dead bodies. In some cases men could be seen lying dead in the well. Still no matter what colour the water was so long as we got it. Some of it would be blacker than this ink, on other times it would be brown whilst very often it would be as thick as whitewash and exactly the same colour.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdUnsurprisingly, dysentery broke out in the ranks and George was affected. Despite battling on, George’s condition worsened and he was ordered back from the front line and then to a ship back to England, arriving in Plymouth on September 1915.

His diary ends there, but George recovered, returning to Mirfield. He died aged 67.