How migrants adjusted to the cold on arrival in the Heavy Woollen District

He was part of a large group of Indian and Pakistani nationals who were encouraged to come and work in England’s mills throughout the post-war decades of the 1960s and 1970s. These migrants came due to a severe labour shortage existing at that time across the country.

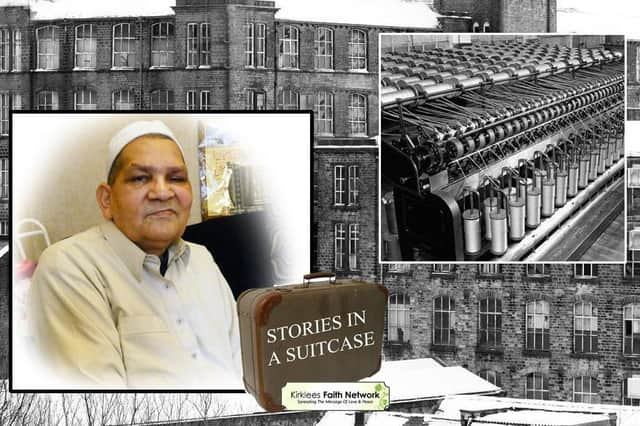

As someone who now makes up a dwindling generation, Mr Nazir has agreed to be interviewed by the Kirklees Faith Network’s “Heckmondwike Stories in a Suitcase” project.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn this third interview, Mr Nazir has spoken to the Reporter Series about the weather of that Sixties decade. He also talks about what life was like working in our local mills.

Mr Nazir said: “I came to England at the age of 15 in November 1963. All I had with me at the time was just £5 in my pocket, and a small suitcase tightly clutched in my hands.

“I can remember it was a cloudy drizzly November in the year 1963 when I first arrived to England - and then into our local Heavy Woollen District - or to put it in more simple words, into the town of Heckmondwike.

“Feeling tired after a long journey, I went to bed early on my very first evening at the house on William Street where I was staying. This small terraced property in the Liversedge area was to be my home for the next several years.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I awoke the following morning to see a thick carpet of white snow outside. The sudden change in weather really surprised me as someone who had only just arrived a day ago from a humid Sub-Continent’s climate.

“It was the first time ever I had seen any snow!

“As I settled down to a new life in England, I saw heavy snowfalls beginning every year from the end of November onwards. It often continued snowing until March or even April!

“The winters were much colder in those decades. Today’s weather cannot even be compared to what we saw in that period.

“The wintry weather of that time really tested our nerves.

“I saw snow up to four feet deep in my lifetime.

“Traffic on the roads used to get gridlocked on most days. Whatever cars there were at the time in the streets got stuck in the snow.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Engines went cold and petrol even solidified on occasions if the freezing temperatures dropped severely.

“The impact of those cold 1960s winters was felt just as heavily inside our homes as it was outside! We were living in small terraced houses with no insulation and no central heating.

“The strong winds blowing outside often made our windows vibrate with a haunting noise. Only one thin sheet of glass - sealed with some putty - kept us apart from the plummeting cold temperatures outside.

“Double-glazed UPVC windows and boilers did not exist at that time to protect us from the elements.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“The chilling winter’s air was felt everywhere. A cold draught always came through the wooden window frames, and from under the doors.

“The only thing we had to keep warm were sacks of coal stored in the cellars. A handful of this murky stuff was always brought up and put into the fireplace before it got lit up.

“Despite the cold, we walked to work during those harsh winters.

“I was on ‘nights’ for seven years at a mill called ‘T Smith’s’ in Batley.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I later joined the huge workforce at T A Firth’s in Heckmondwike where I began doing eight and a half hour shifts from Monday to Friday. Weekend work was sometimes available because the mills were so busy in those days.

“Our white English-speaking workmates on the shop-floor simply knew us as ‘the Asians’. But the Pakistani migrants were actually made up of two different generations of mill workers.

“There was obviously the first generation of old soldiers who had served in the British-Indian Army during the Second World War.

“Then, a much younger group of ‘Asian’ men like me also began working in the local factories especially from the mid-1960s onwards.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“I was a part of this Pakistani second generation who had to work between six to twelve hour shifts.

“Like everyone else, I had to ‘clock in’ when starting my shift, and then ‘clock out’ at the end when it was time to finish and go home.

“I spent most of my working life in the textile industry doing manual jobs like ‘doubling’ and ‘spinning’.

“Half an hour was given to all the workers to have our lunch. We also got two tea-breaks during the eight-hour shifts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But there were no coffee machines or canteen facilities in most of the old traditional 19th century mill structures.

“Instead, we bought our own tea from home in a warm thermostat. The chapattis and curry were packed in our steel tiffin cans.

"We ate sitting next to our work space which was usually warm enough because of the large metal pipes fixed above us on the ceiling. I had no idea why these huge pipes were fitted all around the buildings.

“Big, medium or small, the Victorian era mills were everywhere and open to full capacity in our time. In fact, a long stretch of Bradford Road was dotted with these workshops and factories.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"I can still remember very clearly the roofs of all these different mills used to dominate the skyline of Batley and Dewsbury.

“No local war veterans’ associations seemed willing to open up their doors for our elderly first generation, whilst the local working men’s clubs were ‘no go’ places for us younger Pakistani men.

“So, everyone would meet up in one house where we spent our weekends taking to each other about anything and everything. Young and old, all of us came together on our days off work.

“We did not mind sitting in the same room as our elderly first generation. My age group looked up to them with affection and respect.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad"The age gap did not really matter in that era. There was instead a very strong community spirit existing amongst us.

“Some of the old soldiers would tell us wartime stories about their experiences as captives held in the Japanese POW camps. These veterans used to remind us of a time when they had to stay alive by planting and eating wild spinach in these camps.

“We were taught that life in post-war 1960s England was perhaps far from perfect when it came to the weather.

“But at least it was much better than spending time trying to survive in a Japanese prisoner of war camp.”